A pork industry in the throes of change

For several decades now, the pig farming industry has been facing up to major challenges as it embarks on a process of continuous improvement in terms of animal welfare, food safety, consumer image and environmental impact1.

As Europe’s 3rd largest pork producer, with 2.1 million tonnes of pork to be produced by 2023, the pork industry remains a buoyant, economic sector2. What’s more, pork still accounts for 38% of meat consumption, making it the most widely consumed meat in the world.

However, the pork sector is threatened by the constant emergence of new diseases, which can become a cause for concern. It has become necessary for operators in the pork industry to have a protocol in place, enabling the conservation of breeds in the event of epidemic outbreaks, whether in the wild or on production farms.

The Cryopig project: what’s in it for the pig industry?

The aim of the Cryopig project, launched in 2020 in partnership with VetAgroSup, ISARA Lyon and IFIP, is not only to create new scientific knowledge in the field of pig reproductive biotechnology, but also to propose industrializable solutions to the challenges facing the pig industry today.

The study of this still innovative field is a strategic and long-term development axis for the Axiom Group. One of the reasons for this is to safeguard pig breeds, in order to preserve the heritage and genetic diversity of the herd. In the longer term, it is possible to imagine a new tool for genetic dissemination.

This could alleviate the various problems associated with transporting live animals, by focusing solely on maintaining optimum temperature during embryo transport.

In the longer term, it would be possible to envisage the creation of “response” centers to speed up the re-implantation of a breed, or the reconstitution of an entire herd after its disappearance due to a particularly virulent epidemic, as was the case in China with ASF (African Swine Fever) in 2018.

The National Cryobank, a contributor to safeguarding genetic variability

It was against this backdrop that a cryogenic pig seed bank was set up several years ago within the National Cryobank (Cf. CRB-Anim). But reconstituting an endangered breed or a specific genetic line requires cryopreserved embryos or oocytes. A cryobank of this kind also makes it possible to manage swine genetic diversity, to make long-term use of these resources, and in particular to safeguard local breeds with low numbers, whose situation remains critical in the face of current health risks.

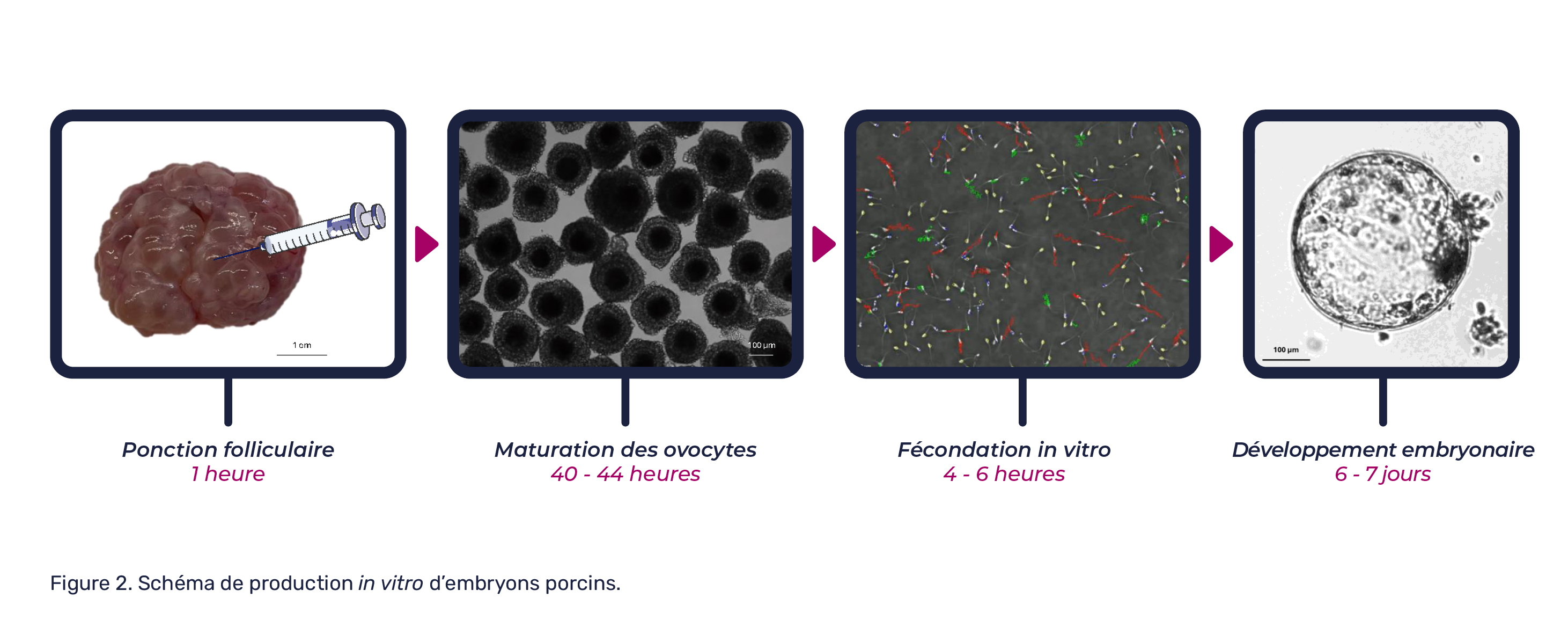

Let’s move on to the scientific aspect of this method, by exploring the research carried out by our teams on the stages of in vitro pig embryo production.

Although the first successful in vitro production of pig embryos dates back to 1986, the success rate remains relatively variable. The main challenges encountered in the porcine species are the high incidence of polyspermia*, embryo stalling at the four-cell stage (a stage associated with embryonic genome activation in mammals) and low blastocyst rates3.

Controlling and transforming the composition of culture media (maturation, fertilization and development) is a key factor in overcoming these obstacles. Post-thaw embryo survival has been shown to be highly dependent on culture systems5. Finally, the proper in vivo development of an individual depends on the correct establishment of its first cell lines, since it is these that will enable implantation8 and fetal development.

« The scientific objective of this project is to characterize the effects and study the interactions of factors that currently compromise the in vitro production of porcine embryos and their cryopreservation, with the ultimate aim of preserving embryos »

Cryopig, what are the main steps in a protocol designed to increase the number of embryos successfully transferred after cryopreservation?

The thesis project is organized as a “cascade”, with the knowledge acquired at each of the different stages of in vitro production (maturation, fertilization, development) and cryopreservation of porcine embryos enabling us to move on to the next.

Step 1: What factors affect the development of in vitro-produced embryos?

Current literature shows that there is currently no universal protocol for in vitro production in pigs, mainly due to the absence of chemically defined media, the use of natural products and the uncertain role of numerous additives in these media3. As a result, in vitro embryo production rates are relatively low in the vast majority of experiments. At the same time, embryo stage and quality remain largely undetermined.

The aim of this first stage is therefore to identify all the factors likely to impact on the development of these embryos, right up to the desired embryonic stage. One of the avenues envisaged is the adaptation of culture media. In this way, the embryo could benefit from different additives at different stages of its development, through the use of sequential media. Instead of using a single medium for the whole of its in vitro development, the composition of the media could be varied over time to better mimic the needs of the embryo in vivo, according to its stage of development.

Since the embryo does not require the same inputs throughout its development, adding or removing certain molecules at key stages could have a beneficial effect on blastocyst formation*.

Step 2: What are the optimal conditions for cryopreserving in vitro embryos?

Cryopreservation protocols are based on the use of solutions that protect the embryo from the harmful effects of the physical phenomena of freezing, the nature and concentration of which vary considerably according to the systems studied.

Incubation times in these solutions, as well as adapted cooling and reheating methods (slow freezing, vitrification) can also have an impact on embryo survival.

The aim of this step is to identify the effects of each of these parameters on the survival of embryos produced in vitro (morulas or blastocysts), as well as their interactions, in order to establish a cryopreservation protocol adapted to porcine embryos. To this end, the toxicity of cryoprotective solutions will be assessed on embryos produced in vitro, without the application of cooling and reheating steps. This step will enable us to draw up a list of solutions with no (or negligible) adverse impact on the maintenance of the embryo after cooling and before rewarming.

Step 3: The impact of the various factors studied above on the transfer conditions for embryos produced in vitro and then cryopreserved.

Having identified the optimum conditions for cryopreservation of in vitro-produced porcine embryos, the aim of the third stage is to identify the markers characteristic of the embryos’ development potential and therefore of their quality.

The expression of pluripotency genes (such as Oct4, Nanog, Sox2, Cdx2)4 will be assessed in order to observe the establishment of the first embryonic layers (inner cell mass and trophectoderm) required for the in vivo development of a new individual8. The expression of these genes is crucial for the establishment of the organism’s organizational plan, which is essential in the early stages of gestation.

The particular anatomy of the sow’s genital tract has made it difficult to develop simple, non-invasive, or at least minimal, transfer procedures. Over the last decade, new procedures have been developed which allow non-surgical embryo transfers while effectively preserving the embryos. The absence of surgery and the preservation of embryos at this stage are essential to meet societal expectations linked to animal welfare6. Thus, the cryopreservation protocols that deliver the best results will be selected for the production and cryopreservation of porcine embryos.

As part of the Cryopig project, the transfer method envisaged will be a non-surgical one, with a deep intra-uterine deposition site6. Gestation follow-up will be carried out to confirm embryo implantation and development. For pregnant sows at term, farrowing survival rates will be calculated, and longitudinal monitoring (weekly ultrasound examinations, hormonal profiles) over the 115 days of gestation will confirm that no abortions have occurred.

Conclusion

Overall, the development of this technology and the creation of effective protocols at every stage opens up a host of possibilities, and the development of a new genetic dissemination tool that will revolutionize transport and the pig industry as a whole.

Editor(s)

Article written by Victoria Slezec-Frick, PhD at Axiom and VetAgroSup.

- Article popularized by Axiom’s Communications Department.

A few tips to help you understand the article better

Cryobank: a bank (in this case of sperm and embryos) for cryogenic storagewith the aim of preserving species.

Ovocytes: Scientific term for the ovum.

In vitro: Refers to chemical, physical or immunological reactions or all experiments and research carried out in the laboratory, outside a living organism.

Polyspermia: Penetration of an oocyte by more than one spermatozoa. This can lead to later developmental problems. It is the opposite of monospermia, which is the normal natural phenomenon of a single sperm penetrating an oocyte.

Blastocyst: A very early stage of the embryo, after the morula stage, called blastocyst when it has the beginnings of a cavity in its centre. This is usually the last stage that can be observed in vitro. In pigs, the blastocyst can be observed microscopically from the 5th day after fertilisation.

Morula: A very early stage of the embryo, called amorula when it has 16 to 32 cells and no central cavity. In pigs, the morula can be observed microscopically from the 4th day after fertilisation.

Trophectoderm:Name given to certain cells of the blastocyst during early embryonic development. These cells enable the embryo to implant in the maternal endometrium. It is also at the origin of foetal membranes such as the placenta.

Inner cell mass: Name given to certain cells of the blastocyst during early embryonic development. Some of these cells are involved in the development of the foetus.

Sources and bibliography

Bidanel, J.-P., et al., 2020. Cinquante années d’amélioration génétique du porc en France : bilan et perspectives. INRAE Prod. Anim., 33. https://doi.org/10.20870/productions-animales.2020.33.1.3092

Eurostat et douanes. https://lekiosque.finances.gouv.fr/Default.asp

Fowler, K.E., et al., 2018. The production of pig preimplantation embryos in vitro: Current progress and future prospects. Reprod. Biol., 18, 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.repbio.2018.07.001

Hall, V.J., 2013. Early development of the porcine embryo: the importance of cell signalling in development of pluripotent cell lines. Reprod. Fertil. Dev., 25, 94. https://doi.org/10.1071/RD12264

Lowe, J.L., et al., 2017. Supplementation of culture medium with L-carnitine improves the development and cryotolerance of in vitro-produced porcine embryos. Reprod. Fertil. Dev., 29, 2357. https://doi.org/10.1071/RD16442

Martinez, E.A., et al., 2019. Achievements and future perspectives of embryo transfer technology in pigs. Reprod. Domest. Anim., 54, 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/rda.13465

Mucci, N., et al., 2006. Effect of estrous cow serum during bovine embryo culture on blastocyst development and cryotolerance after slow freezing or vitrification. Theriogenology, 65, 1551–1562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2005.08.020

Surani, M.A., Barton, S.C., 1977. Trophoblastic vesicles of preimplantation blastocysts can enter into quiescence in the absence of inner cell mass. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol., 39, 273–277. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.39.1.273